Junior Biology major Kendall Byrd is pictured with a pine snake.

By Dr. Zach Felix

Sitting in his white antebellum house in Cherokee County, Tommy McFarland talks about the first Bull Snake he ever saw:

“I was by myself. We lived down there on Mack Chastain’s place (in Nelson). I was 11 year old (sic) then. I walked out in the woods to get some firewood with an ax. I was walking around looking and something went ‘whoosh.’ I looked down, and there was a Pine Snake about that big around coiled up in the leaves. I walked right up on it. It blowed (sic) at me, and I throwed (sic) down the ax and run.”

The animal McFarland speaks of is the Northern Pine Snake (Pituophis melanoleucus), often called the Bull Snake. This name likely comes from the snake’s unique ability to blow or hiss loudly—a sound, as McFarland has shown, even 60 years later, one will not soon forget. Herpetologist Bryan Hudson, of Roswell, explains, “In talking with other folks who grew up in North Georgia during the 1950s and 1960s, we often hear that while they have not seen a Pine Snake in many years, they can recall frequently encountering these Bull Snakes while out working in farm fields.”

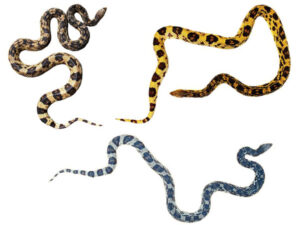

This is a large snake, thick-bodied and stretching to lengths over 6 feet. They are a harmless, nonvenomous species sometimes confused with Timber Rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus); the latter being a much heavier bodied snake with a very different pattern than that of the Pine Snake. The Pine Snake’s color is a dark brown to black pattern on a cream-yellow or tan to white background. The color pattern is very bold for such a large snake and can best be remembered by the rule of three. Imagine one of these snakes stretched out in a straight line and divided into three equal lengths. The first third or head third exhibits a heavily mottled or freckled pattern that does not appear to have any definable shape. The middle third or body third starts to develop a recognizable pattern, usually in the form of dark oval or square shapes. The last third or tail third is the key to identifying a Pine Snake. This section has very distinct oval or circular dark blotches that extend to the very tip of the tail.

Kelly Vickers, a long-time resident of Stephens County, Georgia, reflects on his first encounter with a wild Pine Snake while walking Hudson to the site:

“This was a green grassy meadow, part of our farm where we grew hay and corn. It was one day when we were up, one summer, and I was putting nitrogen pieces at the base of each stalk of corn. The road continued on through here, before the trees of course. There was an area to the right probably about 50 yards long by 30 yards wide, another little strip also in corn. It was in that corn patch that we caught a very large, about 5-foot Pine Snake. It was the summer of 1976.”

The Northern Pine Snake is a large snake, thick-bodied and stretching to lengths over 6 feet. They are a harmless, nonvenomous species sometimes confused with Timber Rattlesnakes.

These conversations, combined with field work, indicate that, while now rare, Pine Snakes were a fairly common inhabitant of rural areas of North Georgia in the past. This decline is likely due to changes to the snake’s habitats across the region. A very similar story explains why the Bobwhite Quail (Colinus virginianus) is now rarely encountered in North Georgia.

According to Dr. Ken Wheeler, Reinhardt University professor of history, “The forested landscape of northern Georgia today is tremendously different from what existed just decades ago. In 1940, for example, Cherokee County had well over 1,000 working farms. And many trees were part of orchards. Cherokee County farms at that time had over 31,000 apple trees and another 25,000 peach trees. The situation was similar over most of the northern part of the state.”

McFarland adds that “The woods around here used to be a lot cleaner than they are because they got burned off every year. It kept the undergrowth off and then when a fire did get started it didn’t kill the big trees. But there were more berries, things to eat, simply because they burned the woods off.”

The Northern Pine Snake can be thought of as an emblem of rural North Georgia, a species associated with dirt roads, working forests and small farms. They are a “Good Old Days” kind of animal. Along with other species such as Bobwhite Quail and Fox Squirrels, are Pine Snakes part of a vanishing community of days gone past, or can they be conserved? How common is the species in our region? What kinds of habitats do they use?

Research based out of Reinhardt University is looking for answers to these questions. Please help these efforts by sharing knowledge about Pine Snakes. This could be an opportunity to prevent this important species from becoming rare enough to be listed as an Endangered Species, and to conserve this important component of our cultural and natural heritage.

+++

Zach Felix, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of biology at Reinhardt University in Waleska, Georgia. He has studied reptiles and amphibians for 20 years and is interested in all things zoological. Felix lives in Ball Ground with his wife and two daughters.

Bryan Hudson earned a M.S. in Biology from Georgia College in Milledgeville and is a prospective doctoral student at Clemson beginning in the fall. Hudson is from Roswell and has been chasing the elusive northern pine snake since he was a child.