Many faculty members have taught at Reinhardt University in its history. One important figure who worked in Waleska in the middle 1890s was Rosa P. Chiles, who helped shift Reinhardt University from its founding idea centered around railroad and town development to a different conception that emphasized Reinhardt as an isolated mountain school, a missionary outpost among a deserving population in need of education. Chiles promoted that idea through a novel she published in 1900 and her idea of Reinhardt became the dominant identity of the school from the beginning of the 20th century into the 1940s.

After the Civil War, entrepreneurial Georgians worked hard to recreate the state and bring prosperity. In Waleska (spelled as “Walesca” in the nineteenth century until the federal government renamed the post office around 1900), John Sharp ran a store, speculated in real estate, invested in a gold mine and a lime kiln, and, significantly, backed a proposed railroad, the Kingston, Walesca, and Gainesville Railroad, designed to run east and west across northern Georgia. Augustus Reinhardt, whose sister Mary Jane had married Sharp, practiced law in Atlanta, also owned a gold mine and developed real estate, and joined a trolley car company that provided many of the backers for the anticipated railroad. Augustus Reinhardt also built a hotel in Waleska and financed the minister and teacher who led the school, which was just one component of this booster dream of growth and prosperity.

That vision worked for a decade, from 1883 to 1893, when it all came apart in a national economic depression, the Panic of 1893. In Georgia, cotton prices hit record lows and the economy collapsed. Augustus Reinhardt’s leveraged properties in Atlanta sank in value and he was forced to sell them at huge losses. The anticipated railroad across northern Georgia was never built. Augustus Reinhardt’s Waleska hotel caught fire and burned and he had no insurance on it. In 1896, John Sharp died. The vision of a forward-looking, growth-oriented college rising amidst general prosperity in a railroad town had been smashed by powerful economic forces. What would come next?

Rosa P. Chiles, a Virginia native born in 1866, came to Georgia in her twenties. In 1893, then-Reinhardt Normal College hired her, and she worked for the next few years as an instructor of French and English. Chiles also ran the library and helped students put on plays. Joseph Mahan, who knew people who had studied with Chiles, described her as “the ideal of the Reinhardt girls in the early eighteen-nineties. Her soft-spoken, cultured voice seemed to achieve the ultimate in perfection of spoken English and her every mannerism was graceful and showed careful training. In addition, she was sweet and kind.” When Chiles departed in 1896, students formed the Rosa P. Chiles Literary Society, a sure sign of their admiration for her. Beyond her teaching, Chiles also wrote a novel set in the area. As she wrote to her cousin William Bibb in 1895, “Dear Will, I have written a book of considerable length, and am anxious to have it published immediately . . . My story is in the “cracker” dialect, fresh and attractive.” (The word “cracker,” often used in a derogatory sense today, has had a variety of meanings over centuries. Chiles seems to have meant it to indicate rural, often poor, whites, but did not mean to use the term negatively.) Chiles wanted a loan of $250 to publish her book, which she expected could appear the next month. Cousin Will must not have loaned Chiles the money–it took another five years for her work to appear. Down Among the Crackers presented Reinhardt Normal College not as a gem in a bustling town expecting a railroad in a countryside studded with gold mines, but as a noble Christian effort in the mountains, surrounded by a population of people who were often sweet and kind, but also included desperate men who ran moonshine stills and lazy men who made their wives work the farm. Instead of describing promising gold mines of the sort that Augustus Reinhardt and John Sharp invested in, Chiles wrote about men who would wash sand from creeks and seek tiny grains of gold, which they stored in goosequills and took to the store to exchange for tobacco and other goods.

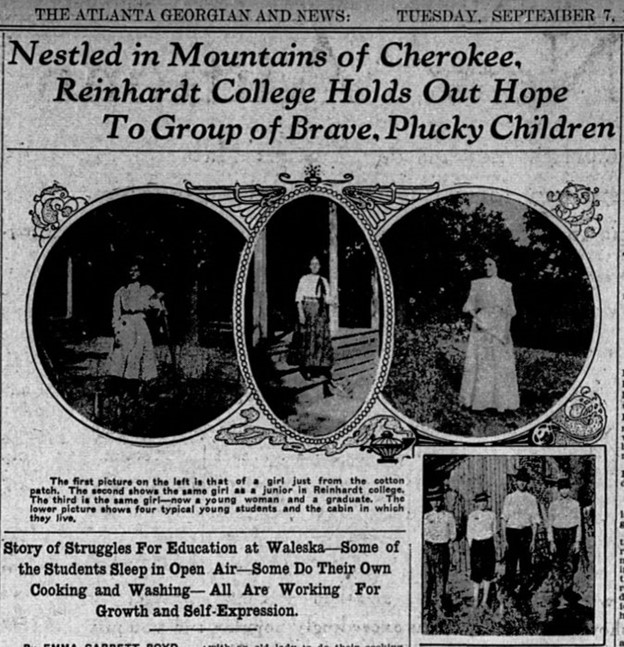

This vision of Reinhardt that Chiles illustrated and the work it did among less educated folk living in the hills and mountains apparently appealed to donors. The next generation of leadership at Reinhardt, in the form of President Ramsey C. Sharp (son of John and Mary Jane Sharp, and nephew of Augustus Reinhardt), took this vision of a remote mountain school and made it a centerpiece of the idea of the school. In 1904, Ramsey Sharp asked for help from the Methodists so that Reinhardt teachers could continue “carrying a Christian education to these noble boys and girls, lost in the mountain forests of north Georgia.” Reinhardt began a “Mountain Boys’ Loan Fund” to assist worthy students. In 1909, an Atlanta newspaper headline read “Nestled in Mountains of Cherokee, Reinhardt College Holds Out Hope to Group of Brave, Plucky Children,” some of whom were camping in the open air at Reinhardt because they did not yet have sufficient housing. In 1910, Reinhardt began a monthly magazine, the Reinhardt Mountaineer. Some elements of this identity still echo. In 1922, Reinhardt faculty member Dora

Lee Wilkerson composed Reinhardt’s alma mater, which begins “Far up in the mountains azure/ Blest with ideals true.” The following year, 1923, Reinhardt created the “Mountain School Foundation,” a funding organization promoted annually during the 1920s and 1930s. The catalog, written to entice students to enroll, described “the most inspiring mountain scenery” and the “grandeur of the mountains.”

By then Chiles had moved on to a career in Washington, D.C. as an archivist and writer. On one occasion she gave testimony to Congress on the need for what became the National Archives, probably the only Reinhardt faculty member to testify before Congress. Yet her influence lasted far longer than her brief time as a faculty member. We ought to remember Rosa P. Chiles as a significant figure in the early intellectual life of Reinhardt University, and as someone who reshaped the identity of Reinhardt from its booster origins into a mountain school, the home of the “brave, plucky children,” some of them sleeping under the stars as they sought a meaningful education in Waleska.

Written by Kenneth Wheeler